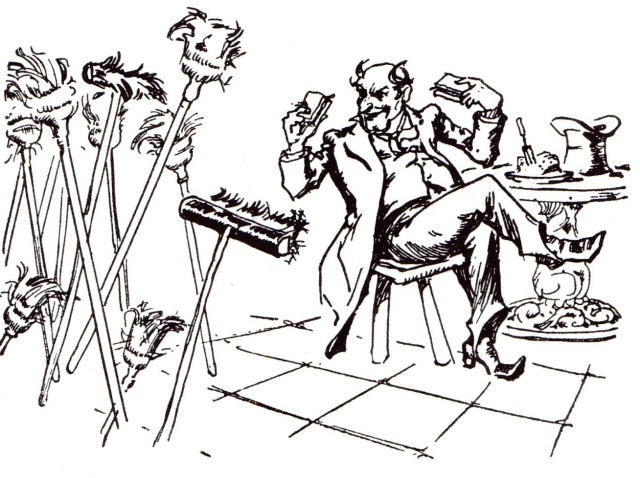

The Oz series in general is big on having normally inanimate objects walk and talk, from the Scarecrow and Tin Woodman in the first book on through living beings made of wood, glass, stone, smoke, ice and snow, foodstuffs, and so on. It’s in John R. Neill’s contributions to the series, however, that such things appear to be the norm rather than the exception. The houses in the Emerald City can move to a certain extent and even fight each other, rivers can obey commands or purposely disobey in order to cause trouble, shoes sing and play instruments, brooms can move and communicate, and even a rubber band can spring around the room and argue.

There’s some precedent for this sort of thing in earlier books, but Neill definitely takes it to extremes.

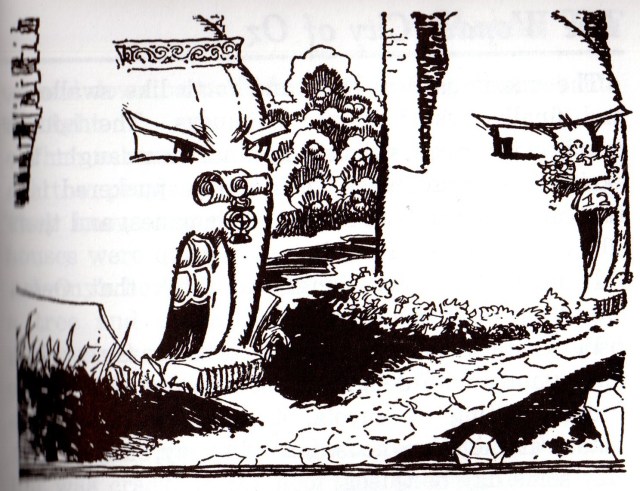

W.W. Denslow drew the houses in Oz looking like they had faces, and Neill followed suit in his own illustrations. This was probably partially why they were so autonomous in Neill’s books. In The Wonder City of Oz, when Jenny Jump looks for a house in the city, one of them rejects her and another welcomes her. Later, the houses get into a fight, hitting each other with various objects. Number Nine seems to regard such a battle as unwelcome but not totally unusual, and after the fight ends the buildings all pull themselves back together again. As far as I know, though, these houses never talk; and at one point the text says, “This made the other houses so angry that they would have shouted, if there hadn’t been a law forbidding them to do so.” While much of this might have been added by the editor, Neill did supply one picture of two houses glaring at each other, and another of a block in ruins.

I understand that Neill’s next two books weren’t edited that heavily at all, and both also contain references to self-aware houses.

Scalawagons has Ozma speak of “an impertinent house in Apple Alley that keeps its shutters closed all day and open all night.” And in Lucky Bucky, the city’s houses wake up in the morning, stretching their chimneys and yawning with their front doors. Jenny’s house is particularly active, making meals for its owner, sweeping the floors, and capturing invading Nomes with its chimneys. A moon-shaped clock tries to cover for Number Nine when he’s late for work, and slips away into the bakery across the street once it gets caught. As Joe Bongiorno points out, Number Nine’s family regards the self-maintaining house as a novelty, so this might not be the case throughout Oz. It might not even be true for other dwellings in the Emerald City. When Jenny first becomes half-fairy, she “could hear the chairs talking to each other” in her New Jersey home, and it’s certainly possible that her powers magnified the already-existing signs of life in her Emerald City house, making it even more magical.

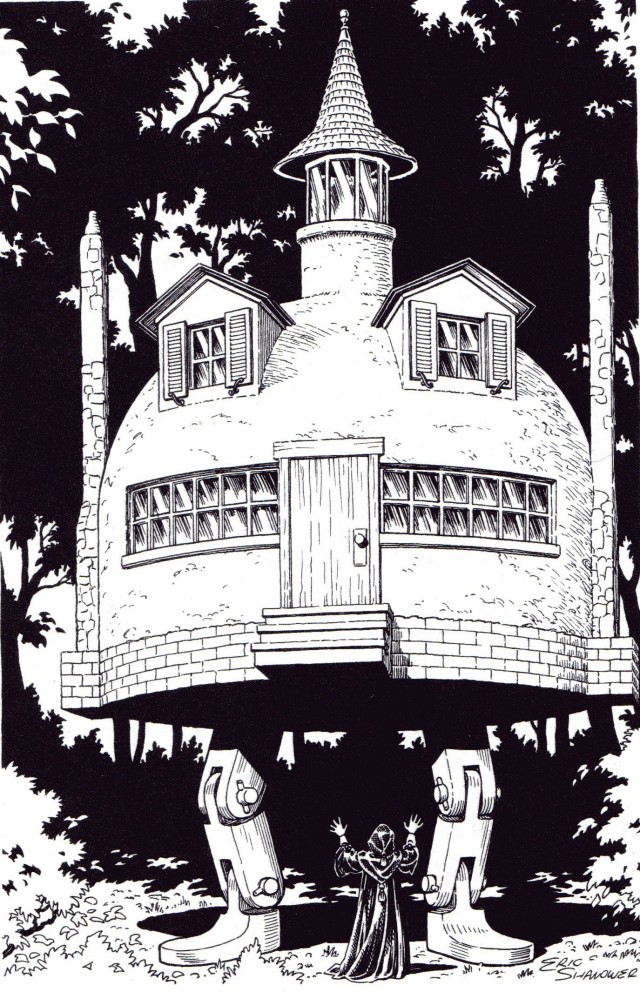

More recently, Edward Einhorn wrote a book called The Living House of Oz, in which not only the titular house is alive, but so is all of the furniture. Here, however, it’s presented as an anomaly, and its owner Mordra is said to have used Dr. Pipt’s Powder of Life to animate it. It’s possible that the Powder or some other life-giving substance had accidentally gotten into the homes in the Emerald City prior to the Neill books. If this is the case, they presumably remained alive after this, because otherwise someone would have taken life from sentient (or at least semi-sentient) beings. Perhaps Ozma, Glinda, and/or the Wizard of Oz found some way to calm them down so that they stopped fighting. As for the rivers, well, Singra encounters a water nymph in Rachel Cosgrove Payes’s Wicked Witch, and river elementals feature prominently in Dick Martin’s Ozmapolitan.

Not that Princess Melody, ruler of the Winkie River, would ever bring witches and Jinkijinks (whatever those are) to pester the Scarecrow and Tin Woodman, but maybe some malevolent force had taken control of the waterway.

It does seem like there might be certain levels of life in Oz, which is why someone like the Scarecrow can be a full-fledged character, while things like the houses in the Emerald City have some personality traits without full sentience. I refer you back to things like the backwards road and Trick River in Patchwork Girl, or the various willful roads in Ruth Plumly Thompson’s books. They appear to be somewhat aware of what’s going on and capable of moving on their own, but don’t necessarily really think. The fact that most of them can’t talk might well be related, although not talking doesn’t necessarily mean a lack of intelligence. For instance, King Kinda Jolly’s pet footstool Trippsy doesn’t talk, but appears to be fairly smart.

Pingback: Foresight Is 2020 | VoVatia